Last year I ran into a problem with IMS LTI in some versions of Internet Explorer. It turns out that my LTI tool was assuming it was OK to save cookies in the browser but IE was assuming it wasn't. Chuck has written about this briefly on his blog and the advice given there is basically now best practice and documented in the specification itself. See LTI, Frames and Cookies – Oh MY!

So I just spent the day trying to implement something like this ready for my QTI migration tool to become an LTI tool rather than a desktop application and it was much harder than I thought it would be.

Firstly, why is this happening? Well if your tool is launched in a frame inside the tool consumer then you are probably falling in to the definition of 'third party' as far as cookies are concerned. There is clearly a balance to be had between privacy and utility here. If you think about it, framed pages probably know who framed them and so something innocuous like an advert for an online store could use cookies to piece together a browser history of every site you visited that included their ad. That's why when you visit your favourite online store after browsing some informational site to do product research the store seems to already know what you want to buy.

Cynics will see a battle between companies like Google and Amazon who make money by encouraging you to find products online (and buy them) and Microsoft who are more into the business of selling software and services, especially to businesses who may not appreciate having their purchasing department gamed. Perhaps it is no wonder that Amazon found themselves in court in Seattle having to defend their technical implementation of P3P.

It turns out that IE can/could be persuaded to accept your tool's cookie if your tool publishes a privacy policy which IE isn't able to parse. I don't want to appear too dismissive but I simply cannot understand how decisions about privacy can be codified into policies that computers can then read and execute with any degree of usefulness. Stackoverflow has some advice on how to do it 'properly' if you are that way inclined, however.

For the rest of us, we're going to have to get used to the idea that cookies may not be accepted and follow Chuck's advice to workaround the issue by opening a new window. It isn't just IE now anyway, by default Safari will block cookies in this situation too. Yes, the solution is horrible, but how horrible?

Some time ago I wrote some Python classes to help implement basic LTI. That felt like a good starting point for my new LTI tool. Here's Safari, pointing at the IMS LTI test harness which I've just primed with the URL of my tool: http://localhost:8081/launch

In the next shot, I've scrolled down to where the action is going to take place. I've opened Safari's developer tools so we can see something of what is happening with cookies.

So what happens when I hit "Press to Launch"? It all happens rather quickly but the frame POSTs to my launch page, which then redirects to a cookie test page. That page realises that the cookies didn't stick and shows a form which autosubmits, popping up a new window with my tool content in. The content is not very interesting but here's how my browser looked immediately after:

There's a real risk that this window will be blocked by a pop-up blocker. Indeed, Chrome does seem to block this type of pop-up window. In fact, Chrome allows the original frame to use cookies so on that browser the pop-up doesn't need to fire. I only tripped the blocker during simulated tests. Still, it is clear that you do need to consider that LTI tools may neither have access to cookies nor be able to pop-up a new window automatically. To cover this case my app has a button that allows you to open the window manually instead, if I change tabs back to the Tool Consumer page you'll see how my pop-up sequence has left the original page/frame.

Notice that Safari now shows my two cookies. These cookies were set by the new window, not by the content of this frame, even though they show up in this view. They show me that my tool has not only displayed its content but has successfully created a cookie-trackable session.

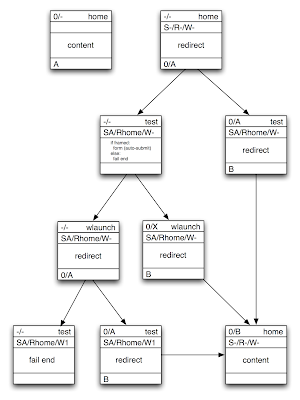

The code required to make this happen is more complex than I thought. I've tried to represent my session construction logic in diagramatic form. Each box represents a request. The top line contains the incoming cookie values ('-' means missing) and the page name. The next line indicates the values of some key query parameters used to pass Session information, Return URL and whether or not a pop-up Window has been opened. The final line shows the out-going cookies. If you follow the right hand path from top to bottom you see a hit to the home page of the tool (aka launch page) with no cookies. It sets the values 0/A and redirects to the test page which confirms that cookies work, outputs a new session identifier (B) and redirects to the content. The left-turns in the sequence show the paths taken when cookies that were set are blocked by the browser.

Why does the session get rewritten from value A to B during the sequence? Just a bit of paranoia. Exposing session identifiers in URLs is considered bad form because they can be easily leaked. Having taken the risk of passing the initial session identifier through the query string we regenerate it to prevent any form of session hijacking or fixation attacks. This is quite a complex issue and is related to other weaknesses such as cross-site request forgery. I found Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) Prevention Cheat Sheet very useful reading!

I will check the code for this into my Pyslet GitHub project shortly, if you want a preview please get in touch or comment on this post. The code is too complex to show in the blog post itself.